In the dimly lit corridors of rehabilitation centers and correctional facilities, an unexpected form of expression has taken root. The Prisoner's Print Project, a grassroots initiative spanning several countries, has given incarcerated individuals an unconventional tool for self-reflection and transformation: printmaking. What began as a small workshop in a Brazilian prison has blossomed into a global movement where prisoners use linocuts, woodblocks, and makeshift printing presses to carve out narratives of regret, hope, and personal metamorphosis.

The textures of these prints tell stories that parole hearings never could. Layers of ink pressed into handmade paper reveal the topography of remorse—deep gouges representing years spent wrestling with guilt, delicate cross-hatching showing fragile moments of clarity. Unlike the performative nature of prison interviews or court-mandated apologies, these images operate in the realm of the subconscious. A former bank robber from Oslo creates a series showing wolves gradually shedding their teeth; a woman serving a life sentence in California prints intricate gardens that grow from the barrel of a gun.

Correctional staff initially dismissed the project as another arts-and-crafts distraction. But as the prints accumulated—displayed in guarded exhibitions that traveled from penitentiaries to university galleries—the psychological depth became undeniable. Forensic psychologists began noticing participants demonstrating increased emotional articulation during therapy sessions. The physical process of carving away negative space to reveal an image provided a tangible metaphor many prisoners had struggled to articulate verbally.

The project's most profound impact emerges in its handling of time. Incarceration distorts temporal perception—days blend into indistinguishable units marked only by meals and headcounts. Printmaking reintroduces deliberate slowness. A single multi-layered reduction print might require weeks of planning and execution, each color layer representing a distinct phase of contemplation. This measured creation stands in stark contrast to the impulsive decisions that often led to incarceration.

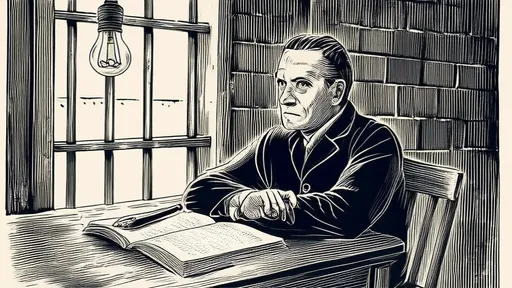

Critics argue that such programs romanticize criminality. Yet the prints themselves resist glorification. The recurring motif of barred windows appears not as clichéd symbols of oppression, but as self-imposed mental constraints. One particularly haunting series from a Singaporean prisoner depicts elaborate mazes where the exit remains perpetually visible yet unreachable—a stark visualization of the artist's own cyclical thought patterns prior to rehabilitation.

Materials pose constant challenges. Maximum-security facilities prohibit standard carving tools, leading to ingenious adaptations. Dental tools, repurposed cafeteria utensils, and even modified hair clips become precision instruments. The scarcity of materials heightens the deliberateness of each mark—there's no room for careless strokes when acquiring another linoleum block might take months.

The project's international scope reveals fascinating cultural divergences. Scandinavian prisoners frequently incorporate mythological imagery of rebirth, while Southeast Asian participants often employ intricate patterns reminiscent of traditional textile designs. South African workshops produce prints vibrating with political undertones, whereas Japanese inmate artists favor minimalist compositions suggesting Zen philosophy. Yet across all regions, a common visual language emerges—the journey from darkness to light, often represented through evolving color palettes across series.

Perhaps most remarkably, these prints serve as bridges to victims' families. In several documented cases, offenders created sequential images documenting their growing understanding of harm caused. These visual apologies, when shared through restorative justice programs, achieved communication where words had previously failed. A burglar in Devon produced a wordless graphic novel tracking his dawning realization of the psychological trauma inflicted on an elderly break-in victim—images that later played a crucial role in the victim's healing process.

As the project enters its second decade, researchers are compiling the first longitudinal studies on participants. Early data suggests significantly lower recidivism rates among printmakers compared to control groups. More qualitatively, parole boards report that the prints provide unique psychological insights unobtainable through standard evaluations. The very imperfections in technique—misregistered layers, uneven inking—often reveal more about emotional states than perfectly executed images might.

The Prisoner's Print Project ultimately challenges societal perceptions of redemption. These images don't request forgiveness—they document the messy, non-linear path of genuine transformation. When exhibitions display prints alongside artists' statements (written years apart), viewers witness the evolution of consciousness itself. A drug trafficker's early prints scream with defiance; his later works whisper with hard-won humility. The paper bears witness to changes the legal system struggles to quantify.

In an era of mass incarceration, this initiative offers a radical proposition: that within the human capacity for harm exists an equal capacity for reinvention. The prints don't excuse crimes—they map the uncharted territory between who someone was and who they might become. As one participant noted in an interview, "Carving a block teaches you that removal creates the image. I had to remove parts of myself to see what could remain."

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025