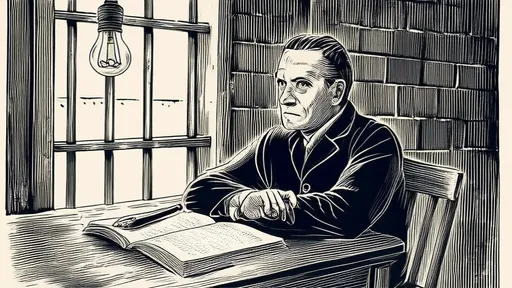

The aftermath of World War II left Germany in ruins—not just physically, but emotionally and culturally. Cities lay in rubble, and the collective psyche of the nation was fractured by guilt, trauma, and the weight of unspeakable atrocities. In this climate of devastation, art became a vital means of grappling with the unsayable. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, a new movement emerged, one that rejected the cool detachment of minimalism and conceptual art in favor of visceral, unfiltered emotion. This was German Neo-Expressionism, a movement that screamed where others whispered, that painted wounds still raw beneath the surface of reconstruction.

The artists of this movement—figures like Georg Baselitz, Anselm Kiefer, and Jörg Immendorff—did not shy away from the grotesque or the chaotic. Their canvases were thick with impasto, their colors violent, their figures distorted as if seen through a lens of anguish. Baselitz’s upside-down figures, for instance, were not mere formal experiments but a deliberate subversion of order, a refusal to let the viewer settle into comfortable interpretation. Kiefer’s monumental works, laden with straw, ash, and lead, evoked the scorched earth of German history, where mythology and Holocaust memory collided. These were not paintings meant to decorate walls; they were meant to unsettle, to provoke, to force confrontation with a past that many wished to forget.

Neo-Expressionism was as much a rebellion as it was a revival. It harked back to the early 20th-century Expressionists—artists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Emil Nolde, who had used distortion and bold color to convey inner turmoil. But where those earlier artists had responded to the anxieties of modernity, the Neo-Expressionists were grappling with something darker: the moral abyss of the Holocaust and the hypocrisy of postwar prosperity. Their work was a rejection of the polite abstraction that had dominated postwar art, a refusal to let Germany’s cultural identity be sanitized. In their brushstrokes, one could trace the anger of a generation that had grown up in the shadow of their parents’ silence.

The movement’s impact extended beyond Germany. In the 1980s, as the art market boomed, Neo-Expressionism found eager audiences in New York and beyond. Collectors were drawn to its raw energy, its unapologetic intensity. Yet this commercialization also sparked criticism. Some accused the movement of being opportunistic, of aestheticizing suffering for the sake of market appeal. Others argued that its masculine bravado—epitomized by Baselitz’s defiant swagger or Immendorff’s politically charged allegories—excluded female voices. Indeed, while women like A.R. Penck’s collaborator, the painter Per Kirkeby, contributed to the scene, the movement remained overwhelmingly male-dominated, a reflection of the art world’s broader inequities.

What endures, however, is the sheer emotional force of the work. To stand before a Kiefer painting—its surface cracked and heavy with debris—is to feel the weight of history pressing down. To confront Baselitz’s inverted figures is to sense the dislocation of a nation unmoored from its own identity. Neo-Expressionism was not just a style; it was a howl against amnesia, a demand that Germany, and the world, remember. In an era when the wounds of war were being papered over by economic miracles, these artists insisted on tearing open the scars, forcing a reckoning that was as necessary as it was painful.

Today, as contemporary artists grapple with new forms of trauma—climate crisis, political extremism, global pandemics—the legacy of German Neo-Expressionism feels strikingly relevant. Its rejection of detachment, its embrace of chaos as a form of truth-telling, resonates in a world that often seems on the brink of unraveling. The movement’s greatest lesson, perhaps, is that art cannot heal what it does not first acknowledge. And in their unflinching confrontation with the darkest chapters of history, the Neo-Expressionists left a blueprint for how to paint the unpaintable, how to give form to the unspeakable.

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025